Primary Palette: Three Powerful Plant-Sourced Pigments

Last year, in preparation for my Waste Not Urine blog and workshop I wrote a lot about Japanese Indigo and how regular application of diluted urine can significantly improve growth rate and lead to more frequent harvesting. I talked about the multi-step process of pigment extraction, and the historically significant role that urine played in the dyeing process. Here, I want to share more about my experience about making paints with this pigment, while also introducing two more seemingly innocuous plants that yield bright and relatively light-fast pigments that can then be blended into an array of homemade binders for surprisingly high quality, artist-grade paints.

Paint: Pigment and Binder

The simplest paints are a combination of just two parts: a pigment and a binder. Pigments are the colorant; they’re the small bits of colored material that are suspended in the binder. Binders are the liquid into which the pigment is blended. Binders are adhesive liquids that dry to form thin layers that ‘lock’ in pigments to form a continuous sheet of color. These days, modern chemistry gives us access to a massive array of binders for many different applications. However, what we’re most interested in here are a few binders that can be readily made with locally-available materials at home:

- Egg Tempera: Sourced from the yolks of hen’s eggs and thinned with water. Egg tempera is a quick drying binder that forms a relatively tough, water resistant paint with a velvety sheen. Egg Tempera was a ubiquitous medium among painters that preceded the European Renaissance.

- Glair: Is the yellow, translucent liquid that drains from standing, whipped egg whites. It is a relatively weak, thin and easily-spoiled binder, but, as an amateur artist it remains one of the easiest to make and work with. Glair was commonly used as an adhesive for gilding, and also as the binder for paints used in the margins of medieval-era illuminated manuscripts.

- Hide Glue: A very strong, heat-resettable glue that is still prized for its application in woodworking projects, when diluted with water makes a binder for soft distemper paints. Historically most commonly used as a size, or as an ingredient in gesso when preparing paper, canvas and panels for paint. Made from animal hide scraps and bones leftover from butchery and the tanning processes.

- Casein: A syrupy glue made from a protein found in curdled cow’s milk. Made when curds are rinsed and dried, then reconstituted in water with an alkali. Like hide glue, casein is a strong glue that works as a paint binder when diluted with water. As an alternative to egg tempera, casein is a slower-drying binder with a water-resistant matte finish.

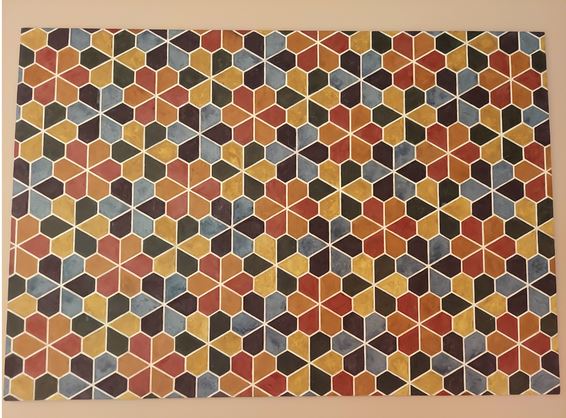

Some of the oldest paints in history are combinations of these binders of animal origin and an earth pigment. Earth pigments are finely crushed stones and clays that yield permanently lightfast colors ranging from greens and yellows, oranges, reds and browns. Historically, brilliant lightfast primary colors were made from a range of minerals and (sometimes very toxic) metal salts like cinnabar and Egyptian blue. In modern times, many of these enduring brightly colored pigments are essentially out of production, replaced by synthetic forms of fossil fuel origin. Luckily for us, as artists interested in locally-available, sustainably-sourced pigments, we have options in plant-sourced pigments.

Plant-Sourced Pigments

There are an abundance of plant-sourced pigments, but relatively few that are considered lightfast. Anthocyanins in beets, red cabbage, blueberries, elderberries and pokeberry for example, boast brilliant blues and pinks when crushed and sieved. However, color from fruit and vegetable juices are fleeting, often turning brown or fading away completely in a matter of months.

Many plant derived pigments are durable. Lasting brown inks can be rendered from black walnut hulls. Charred grape vines (or other carbonaceous materials) can be ground into deep blacks. For bright primary colors, we can rely on millennia of experimentation, chiefly among dyers, that has led to the discovery of more durable and lightfast yellows, reds and blues.

Weld (Reseda luteola)

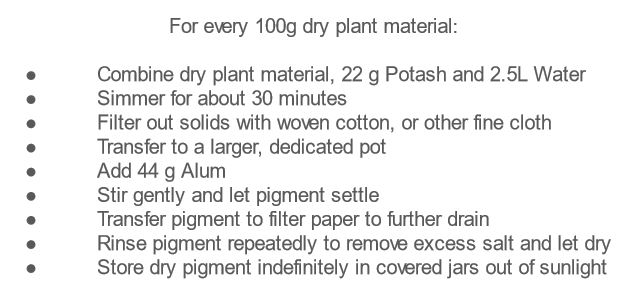

Weld is a ‘weedy’ biennial native to Europe and Western Asia, recognizable by its spiky form and slender cone-shaped flowerhead. Weld is said to yield better pigments when grown on dry, sandy or alkaline soils; it prefers poor soils. Weld propagates easily by seed. Historically cultivated as a dye plant, weld is rich in the flavonoid Luteolin. A deep, clear yellow dye can be obtained when the stalks, leaves and seeds are simmered in water and potash. Dry Lake pigment can be obtained from the liquid dye by binding and flocculating these compounds with alum (potassium aluminum sulfate) or quicklime (calcium oxide).

Weld lake pigment is a very clear, intense yellow that tends to be less than opaque when mixed in binders. For this reason, as with other plant pigments, it was historically used as a layered glaze over other more opaque pigments. Weld lake would have been commonly found in the margins of illuminated manuscripts. Weld lake was used alongside indigo in the (now faded) dark green background of Johannes Vermeer’s famous 1665 portrait, Girl with a Pearl Earring.

Weld lake can be obtained from the plant after just one growing season with this simple recipe:

Madder (Rubia tinctorum)

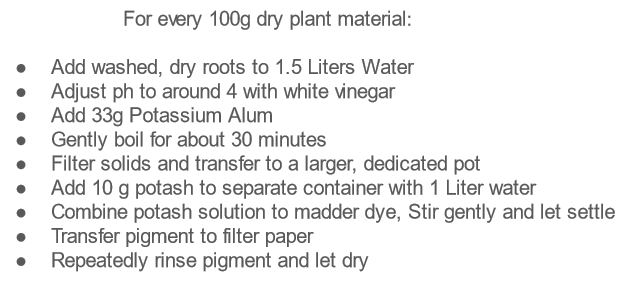

Madder is a herbaceous perennial in the Rubiaceae family. In our Southern Appalachian climate the madder tops die back annually but quickly put on new growth in the spring. A brilliant red dye, rich in Alizarin, can be obtained by boiling washed madder roots in an alum solution. It is believed that higher pigment yields can be obtained when well supported with a trellis and grown in slightly alkaline soil. Madder roots are easier to harvest when grown in pots. Madder roots should not be harvested until after at least 3 years of growth. Upon harvesting, madder can be easily propagated by transplanting a small piece of root and shoot and few leaves.

Madder root is possibly one our most ancient dyes; cloth, dyed with madder was found in the excavated tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh popularly known as King Tut. The red stripes of the American flag were originally dyed with madder. Like weld, madder lake was commonly used in illuminated manuscripts and in oil paintings by Vermeer and his dutch compatriots in the 17th century. Madder, again like weld, is a more transparent pigment that lends itself to over-painting, commonly used as glaze to bring a dimensional look to fabric and upholstery. Vermeer again, used madder lake to accentuate the red lips in Girl with a Pearl Earring.

A madder lake pigment can be made when precipitating the red dye with alum and potash:

Japanese Indigo (Persicaria tinctoria)

Japanese Indigo is a tender, flowering annual, in the Polygonaceae family. Japanese Indigo is just one of a handful of plants that bear significant amounts of the glucoside Indican – the “precursor” to indigo pigment. Indigofera tinctoria, or ‘true indigo’ is a commercially cultivated legume that bears significant amounts of indican. Woad is a common indican-bearing brassica native to Europe.

Indigo is a dye with a rich and vibrant world history. Indigo pigment was likely independently discovered on at least three different continents. Dried blocks of indigo pigment were traded on the silk road and into Europe through northern Africa. Centuries later, indigo was among tobacco and cotton as a major export in the slave economy of the American south. Natural indigo was the original dye of the iconic blue jeans.

Indigo paints are found in many cultures throughout history: Pre-Columbian mesoamerican cultures employed a special technique of blending indigo pigment with an imported clay called palygorskite to create an enduring paint known as Maya blue. Medieval Christian painters used indigo when mineral sources of blue were not available or became too expensive. Again, Dutch contemporaries of Vermeer used indigo along with the other plant pigments for accenting clothing and drapery in oil paintings. “Haint Blue” ceilings of porches in the American South were originally painted with natural indigo pigment.

Japanese Indigo is a fast growing annual that prefers moist, rich, loamy soil. The pigment is found in the leaves, and pigment yield is tied to vegetative growth. It responds well to nitrogen. It is easily propagated via cuttings. A small section of the crop should be allowed to go to seed; Japanese indigo is a plant that is notoriously difficult to germinate after one year. When about 18” tall, the tops can be cut off about 4” above the ground. The tops will bifurcate and grow back more densely for up to 3, or even 4 or 5 harvests in a single season. Pigment can then be extracted from fresh tops through a multi-step fermentation process best described here, but summarized below:

- Cover Japanese indigo stems and leaves with water and keep submerged

- After approximately three days in warm weather, the water will turn an eerie, bright greenish blue and take on a unique sweet, low-tide smell.

- The process is temperature dependent, be careful not to over-ferment.

- Liquid should be filtered and poured into another container.

- Fresh quicklime (CaO, or ‘pickling lime’) should be added at approximately 1 tbs per gallon of liquid

- Liquid should be aggressively aerated for at least 10 minutes.

- After aeration the liquid should become dark blue and frothy

- Pigment should settle within 12 hours, upon which water should be decanted.

- If settling does not occur, incrementally add small amounts of more fresh quicklime.

- Remove pigment paste and continue draining through filter papers.

- Store pigment paste in the refrigerator or dry to store indefinitely in airtight jars.

Plant based pigments will never be as lightfast as their mineral counterparts, but these three plant pigments are among some of the most lightfast plant sourced pigments that are known to exist. I find a unique satisfaction in creating art with materials grown and sourced on my own property – I hope this inspires other gardeners to experience art in this way, and other artists to discover gardening in a new way. If you have insight with growing, extracting and painting with your own plant pigments and homemade binders I would love to hear from you.