Our blog for December is a true story from Living Web Farms’ livestock manager, Rocco Sinicrope.

Let me tell you about the time I caught the steer.

When we were first starting in the cattle business I figured we were a little too small for a cow calf operation. We were, after all just beginning and I had next to no experience. That, topped with the fact that we only had 20 or so acres of grass which is comparatively small and the responsibility of a breeding program was enough to convince me to start off with an all in all out. Granted that jumping in head first does have its advantages when it comes to hands-on learning, but, in this case familiarization of alternative grazing systems was the priority.

All in all out basically means you buy steers and grow them to market weight, then sell the beef. A stocker program like this typically produces beef faster than a breeding system, but you are subject to whatever animals you can find. I was a student of what I’ll call alternative grazing techniques as opposed to the traditional, and I was dying to implement mob grazing, high density grazing, multi species animal impact, and stockpiling grasses for winter. That’s plenty to chew on and get under your belt without having to figure breeding as well. Well, one thing at a time.

So where do we start?

The livestock auction, or sale barn as it’s commonly known, is a fine time. In addition to a place to buy and sell cattle, It often acts as a community hub; lots of information gets passed along there both formally and via casual conversation. I have experienced a strong sense of camaraderie at farmers markets both with other farmers and customers, and the sale barn has the same quality, I think primarily because raising livestock is next-level stuff. I love vegetables and have been raising them for over 15 years, but in my opinion, livestock is more visceral. The energy exchange is more in your face.

For myself at that time however, the mysterious nature was enough to make me look elsewhere. I’m glad I went, and I still go from time to time just to keep myself honest, but I learned that some folks take their best stock there, and some take their worst. The problem for me at the time was my inability to really tell the difference. I kind of figured why not go to the source? Besides, who the hell can understand that auctioneer.

Knowing a little historical background on the animals you are buying and bringing to your farm is useful because it gives you more of an idea of how these animals were raised and the lives they have led. The less they have to adapt to dramatic changes between where they are coming from in correlation to where they are going, the better off they’ll be. This is how I came to meet Tommy Heffner.

I forget if it was Craigslist or the Iwanna (a local bulletin for this kind of trading) but one spring day I found myself headed to upstate South Carolina to meet Tommy who had come highly recommended by some good ol’ Mills River folks. Tommy was a local Henderson County man himself who had moved down off the mountain a few years prior. Presumably to have a little more room to roam and to find some land that was more affordable. I eventually arrive at Tommy’s farm and while driving in I recall being in deep thought, wondering if the rain I was driving through was the hardest I’ve ever seen. I mean to tell you, it was pouring…hard. So after seeing me pull up, he waved me into his shop, we introduced ourselves face-to-face, and from there it was obvious that we didn’t have much else to do but sit down and get to know each other. I also had the chance to meet his wife, Francis and being stuck in their company was such a pleasure. We talked and swapped stories for a couple hours until the downpour subsided and we were able to go look at his yearlings.

Tommy had all the hands-on farm experience that I lacked at the time, and I just sat there like a kid at his feet doing my best to soak in and glean all that I could. I had all these ideas and concepts and theories but finally here was a real opportunity to bounce them off someone with tons of familiarity. I don’t believe any of these ideas were new to him, but it’s fair to say he was more of a conventional practitioner, and if he ever thought my ideas or plans were off the wall crazy, he sure hid it well! It was like free consultation. All-in-all, Tommy turned out to be a great resource for me, especially when I was just getting my feet wet. He was encouraging and supportive, from time to time I’d call on him with a quick question or two or just to say hi, and from time to time he’d do the same.

Tommy has passed on now but as it turned out he was a big fan of frequenting the sale barn. I’m not sure that he did a whole lot of buying and selling although I know he did some, but more to keep up on prices and spend a little time with buddies. I wouldn’t necessarily call this a regret, but as I sit here and reflect on these memories, I sure wish I’d gone to an auction or two with him.

We ended up getting five steers from Tommy and he brought them to us a week or two later. One thing my years of diverse vegetable production has taught me is the concept of staggered harvest via successive planting. It’s nice to have a steady supply of produce coming in over the span of weeks or months as opposed to a one shot deal. For example, the last frost date may be May 15th, but we typically plant tomatoes the entire month, and even into June to stagger the harvest down the line. It also reduces risk because it provides a scenario where plants are coming into and going out of their peak production all at the same time. Why not apply the same philosophy to the steers?

So when Tommy brought us his yearlings I thought I’d bounce an idea off him – would you bring me some older steers Tommy? It made sense to him and at this point he had a pretty good idea of what I was looking for, although he didn’t have any steers that were in the age range I wanted, he said he’d be sure to keep an eye out at the sale barn for me. A few weeks went by, the new steers had gotten accustomed to the frequent paddock moves that make up mob-grazing, and sure enough one day my phone rings and Tommy informs me that he just picked up three big steers for me and he’d see me tomorrow. Great! He shows up the next day, backs into the barnyard and we unload three of the prettiest Charolais crosses I’ve ever seen.

One red, one blonde, one white.

Charolais are a French beef breed. Most American cattle (at least in this area) are some cross of European beef breeds; Angus, Hereford, and Charolais are among the most popular. They unloaded fine and for the most part fell in line with my management system – which includes being moved into relatively small paddocks every 12-24 hours in an effort to maximize efficient use of grass, heavily impact weed pressure, boost fertility, and conserve stockpile grasses for the dormant season. The cattle herd was running with a flock of hair sheep and two donkeys, giving us a flerd. Moving all these animals at least once a day gives you a good rapport with them. Among other things, one advantage in seeing them up close everyday is easy regulation of their body condition. Point is, all these animals were moving along and getting along just fine.

However, there was something that I always noticed. When I would walk out to them for a move, the big white steer would always be the first one to look up and keep his eye on me. Not the five smaller steers from Tommy, not the big blonde or red one, but always that big white. He was always the last to go back to grazing after being moved into a fresh paddock. He would see you from across the farm and never really settle until you were really far away. For the most part, my little flerd was just chugging along that summer. The big white steer never really got too excited about anything, he was just always the first one to stop what he was doing and check you out but he complied and followed all his companions into the next paddock so I never really paid it much attention. Things continued that way for quite a while until it was time to load them for the processor.

Moving livestock somewhere they want to go – like a field full of fresh, lush grass is one thing – moving them somewhere they’re not too sure of is another. A livestock trailer is a prime example. The best way I have found to get cattle loaded is to simply take your time and get them accustomed to it. If you have a handling facility with a loading chute it’s pretty easy to get them loaded, but if like me you don’t, you have to do the best with what you’ve got. Expecting cattle to walk right onto a dark, confined space that they are unfamiliar with can be a tall order, here is my recommendation.

Park your trailer in a location that isn’t out of the ordinary. Secure the wheels and jack so it has no chance of rolling away or shifting when a couple thousand-pound animals walk in it. Prop open the back door in a way that is secure, but allow yourself the ability to shut it quickly and quietly should the opportunity present itself. Put the water trough all the way in the back. Put it in a spot where the livestock have to walk the entirety of the trailer floor to get a drink. Then simply walk away and give yourself a few days for the animals to learn that nothing bad happens to them on the trailer. If you have a date for the processor, or some other reason to move them, just work backwards and set yourself up three or four days in advance to relieve any stress by building familiarity. When the time comes to load them, now they are accustomed with where you want them to go and it’s so much easier than having to force them.

Another little trick that can come in handy is using sweet feed as a little treat for the livestock. Sweet feed is a highly palatable treat for cattle that seems to have the same effect on them as ice cream does for children. Not only can it help to lure cattle, it also trains them that when they get on the trailer a nice surprise awaits them, thereby associating the trailer with good thoughts – a mobile sweet morsel facility, as opposed to a big scary metal trailer. Just feed them a little bit during the time they are getting accustomed to the trailer, and when the time comes to get them loaded, you throw a little in the bin and the cattle come running and you simply shut the door behind them. Done – stress free. It’s just a helpful trick to know and to have in your toolbelt. A couple handfuls in their last days as a treat and to get them where they need to be with no hassle is worth it in my book. To make my point even further I once saw an old-timer load a dozen hogs on a trailer simply by walking on it and they all followed him, then a buddy shut the door, he strolled to the back and his friend let him off. All the pigs ready to go, the whole process probably took 20 seconds. Talk about making something look easy. Amazed, I asked how he did that, it was like magic! He walked over to me, looked me right in the eye and said “son, you gotta be smarter than they are.” He then reached in his pocket and pulled out a crushed up hand full of vanilla wafers.

Learning to work with livestock and how to move them is like learning another language. The more you do it, the more it becomes second nature to anticipate their next move. Always keep in mind that we are not raising predators but prey. Now when you are standing next to an animal that is ten times you size, it’s easy to feel intimidated and for good reason, they can injure people and you should always be careful If bulls and full grown boar pigs were all the size of cat and dogs I think the world would have a lot less farm accidents and there would be far fewer handling and loading issues. My point is that the size of livestock can lead to people being intimidated by the animals they are trying to manage. In and of itself it is a stressful situation that has the potential to get dangerous. Observation leads to understanding, understanding leads to knowledge which in turn enables you to provide the most efficient and stress-free situations for you, the people around you, and the livestock. So to the best of our ability, let’s avoid the scene of scared people handling scared animals.

Livestock and handler engage in a dance to the tune of the animals’ comfort level. You can stand 100 yards from a steer, and while it will notice you are there, more than likely it won’t react because you are too far away to cause immediate threat. Now, standing 12 inches from a steer, you are now close enough to achieve physical contact, and it simply turns into a “too close for comfort” situation and simply goes into a get-out-of-there, flee-as-fast-as-possible state. There is a beautiful and precise point. This one little spot where the animals aren’t stressed, but they don’t want you to come any closer, when one step forward adds pressure and one step back relieves it. That’s where the magic happens, where the dance begins, where you lead and they follow. That precious place fluctuates between species and within species individual animals, but working that edge in a calm manner is the key to handling livestock.

So, back to the due date. The three big steers had been gaining nicely all summer and it was time for them to meet their maker. I had an appointment at the processor and it was time to get them ready for the one-hour ride to Forest City. I put them in the barnyard and set up the trailer. This was the first time I had them in a somewhat confined area – the barnyard is about an eighth of an acre with access to the barn for staples and cover. Anytime I had previously looked or gone in there with them they didn’t get stressed or seem to really pay me any attention, but on loading day, something really spooked big white. I’ve never been able to pinpoint what elevated his stress level so much. The other two were just fine but when I went to load them he ran back and forth the perimeter of the yard, trying to get as far from me as possible while me and the other two steers watched in surprise. I decided to load big red and blonde by getting behind them and doing the dance with their comfort level. A step to the left to make them go right, a step to the right to make them go left, and a couple steps forward and they eased onto the trailer with no significant hesitation. I pushed them all the way forward and closed the middle gate and turned my attention to big white. As soon as I stepped off the trailer, he took one look at me, got a big run and sprinted toward the corner of the barnyard and leaped right out of it, back into the main pasture! I had never seen anything like that before or since. He had been on and off the trailer many times in the previous days but on that day he very clearly wanted nothing to do with it.

I stood there dumbstruck, scratching my head. Well what now? After a few failed attempts to get him back in the barnyard it was clear that he had no intention of cooperating, no intention in fact of letting me even get to a place where I could try and get him to cooperate. It takes a while for animals to calm down after they have experienced high levels of stress, and after an hour or so of running around and trying my damndest to get him back in the barnyard, it was painfully clear that I had lost this battle.

I was a little embarrassed the next morning when I showed up to the slaughter house with two steers instead of three, but they were encouraging and seemed to understand. Apparently I was not the first farmer who couldn’t get an animal loaded, so I made another appointment a few months out and figured I’d try again. The other two big steers had been processed, but Big White wound up back in the rotation with the sheep and things returned to business as usual. Round two approaches.

Fast forward a few months and it would be like rereading the previous couple paragraphs. Now he knew the barnyard wouldn’t hold him and as soon as I even thought about trying to load him, he simply hopped the fence again. It’s not that I couldn’t get him on the trailer; I couldn’t even get him to a place where I could get him loaded. Possibly the most frustrating part was that at this point I’d spent nearly a year with him, providing fresh pasture with daily moves, and he was still untrusting. So I called the abbatoir and had to tell them I would miss yet another appointment, which was embarrassing at this point because it’s basically calling a business you had a deal with and telling them they won’t be making money today because I couldn’t keep up my end of the bargain. Again, they were understanding but I made it a point to say I’ll call you when I’m ready and have him caught as opposed to making another date. They happily accepted.

I’ve had a lot of teachers over the years and they have all helped and contributed in so many ways. It still never ceases to amaze me how people can have two fully functioning regenerative farms, totally successful and have different management tactics. This isn’t a one size fits all sort of thing and there are truly as many farms as there are farmers. One of my teachers is Jim Elizondo. I won’t try to describe Jim’s level of knowledge when it comes to cattle, genetics, and grazing, mainly because I wouldn’t come close to doing him justice, I mean he is really brilliant.

Living Web Farms is an educational farm and we do classes on various subjects for the public and sure enough Jim was coming here from out-of-state to teach a segment on stockpiling winter forage, complete with a little farm tour where we kept the flerd. The morning of the class was cold and rainy and I was full of excitement. While doing chores I had the bright idea to put big white back in the barnyard and add my unsuccessful attempts to catch him as part of a transparent class. Plus, maybe Jim had some bright ideas on how to load him. I hadn’t planned on doing this but convinced myself that it was a good idea although it put me in a bit of a rush. So I hopped in my truck and set up the trailer in its spot, step one. I opened all the gates and doors and made sure they were secure and easily accessible if a lucky opportunity should arise, step two. I ran out to the feed store and picked up a bag of sweet feed. A 50 pound bag is inexpensive and I use it so rarely and infrequently I thought I’d get a fresh one.

With the trailer set up and the lure in place all I had to do was cut out big white from the sheep flock and stick him in the yard. Up to this point, getting him from the barnyard onto the trailer was the problem, not from the pasture to the barnyard, so this shouldn’t be a big deal. Maybe Jim had some secret way to load him and the participants of today’s class can glean some wisdom on animal handling, and I can get this animal on the trailer? A win-win for all people involved right?

Time was against me at this point. It doesn’t take too long to set all that stuff up, but it’s the running around that will eat up your day. I still had to go home, shower, put on some clean warm clothes and be the first one there to greet Jim with open arms and enthusiasm, all while putting on my hospitality hat for our guests while we all learn.

We use electrified mobile fencing or netting for the sheep. They respect it more than the single strand polybraid which a lot of operations use for cattle. I also believe the netting creates more of a mental barrier for the sheep as opposed to just one lonely strand. It is formidable and encourages sheep to stay put. As a quick side-note: sheep can be tough to keep in electric fencing. They are light and agile so they aren’t particularly well grounded (not like hogs or cattle anyway) and they have a heavy wool layer that keeps their skin well insulated from the elements and electricity too. Make sure your fence is real hot when you’re training sheep to respect electric netting.

It can be tricky cutting out different species from one big group. While daily moves are routine at this point and everyone is well accustomed to them, it can still be challenging when you are moving three different species. When the paddock where you want them is right next to the paddock where they are going it’s pretty easy, but there are those times when you have to move them across the whole farm. Our routine at that point was mainly staying ahead of the donkeys because they had the highest level of confidence, not pressing the steer too hard because he is easily frightened, and giving the sheep plenty of space. Moving sheep is interesting, they have the highest flock mentality so when you move them they really unify and act as one being as opposed to a bunch of different personalities.

On this day, the steer was feeling satisfied, and decided he couldn’t be bothered to move anywhere, while the sheep on the other hand were ready to high-tail it across the farm. Why they decided to have such different reactions on what was otherwise a totally normal situation I don’t know, but I have since convinced myself that they had a meeting before I got there and decided to do their best to humiliate me.

Well, they did. At this point I’m rushing. Jim’s class has already started and I’ve been frantically going back and forth around the perimeter of the paddock trying to get the steer out and keep the sheep in. The dance I described earlier is a good analogy, but some days are better than others and I was out there with two left feet. The sheep would get out and the steer would stay, I couldn’t turn my attention to the steer cause the sheep would run off and then I’d have to go get them. Soon as the flock went back in the paddock, the steer wouldn’t go anywhere and if I applied too much activity or pressure, he’d just jump over the netting. It was mildly chaotic and that’s a bad state to be in when you’re working animals.

Again, this is something I do every day with no stress or struggles at all! Why did it have to be today? I was due some humility because right when I was having all those thoughts, at the peak of my frustration of running back and forth around the electric netting, I ran up to it to keep the sheep inside, slipped in the mud right in front of netting, snagged the bottom of the netting with my boot as my feet lifted into the air and over my head, and then came crashing down with a thud, square on my back only to have the netting land right on top of me and give me a couple good jolts until I could crawl out from underneath. I got up and put the fence back together, knowing that I had clearly lost this day. Cold and wet, muddy and tardy, I showed up to my instructor’s class thirty minutes late, a beaten man. Humility served. I spent the class huddled in the back corner kinda hoping no one would notice me. Suffice to say, when it was time for the farm tour I stuck to the subject matter at hand – grazing, not herdsmanship.

There were a couple more unsuccessful attempts that winter and spring which granted the same results, the steer was still around and any new plan of mine to load him proved unsuccessful. It got to the point where I simply didn’t know what to do. I couldn’t get him loaded. In fact, the worst was I couldn’t even get him to a place where I could load him – and he knew it. Big white was well aware of the fact that he didn’t have to do what I wanted him to do and his efforts of distrust resulted in his victory. I really understood the importance of low-stress animal handling, and was basically doing it everyday, but I was beginning to doubt my ability and skill level as a farmer. At least now I can look back and laugh, but at the time it had got to the point where some buddies were making fun of me. I had shared these attempts with people who might actually have some helpful advice and one response was “well, I guess he’s gonna just die of old age.” That one stung a little bit, but I’m thankful for it – because it stuck. A voice inside me said “No. No, he won’t. I’ll get him, one day I’ll get him and I will not give up” I just didn’t know how…

If I recall correctly about a year went by. A full year or so since I missed that initial first slaughter date and it did appear that big white was just gonna have to live here forever. Man, he was big too. We never ran out of grass the whole time and he just lived with the sheep, getting moved everyday and gaining weight everyday. The typical standard weight for steers at slaughter is 1200 pounds live weight. I gauged him to be every bit of 1800 pounds.

One warm evening when the days are nice and long I had finished work for the day and was just piddling around the farm in the cool of the evening when suddenly a thought came to me. Lysondra was in town. Lysondra is a good family friend. She and my wife had met years before when they worked at the same restaurant in Hendersonville. The service industry is something I have no experience with, but they really hit it off and apparently you can develop quite a bond amidst that fast-paced environment. She had moved out of state and was visiting this evening with my wife and kids. Lysondra is a real sharp lady, raised on Staten Island and grew up there in the 80’s; quick-witted and says what she means, she and my wife would have lots to catch up as it had been awhile since they’ve seen each other. I also knew she’d keep my kids occupied because it’s all about family with those two. For me at this moment it meant that I didn’t have to rush home to be with my family because they were occupied, and it was such a nice evening, I didn’t really want to leave anyway. Piddling around thinking about what to do, realizing I didn’t have anywhere to be I said aloud: “I’m gonna go catch the steer”.

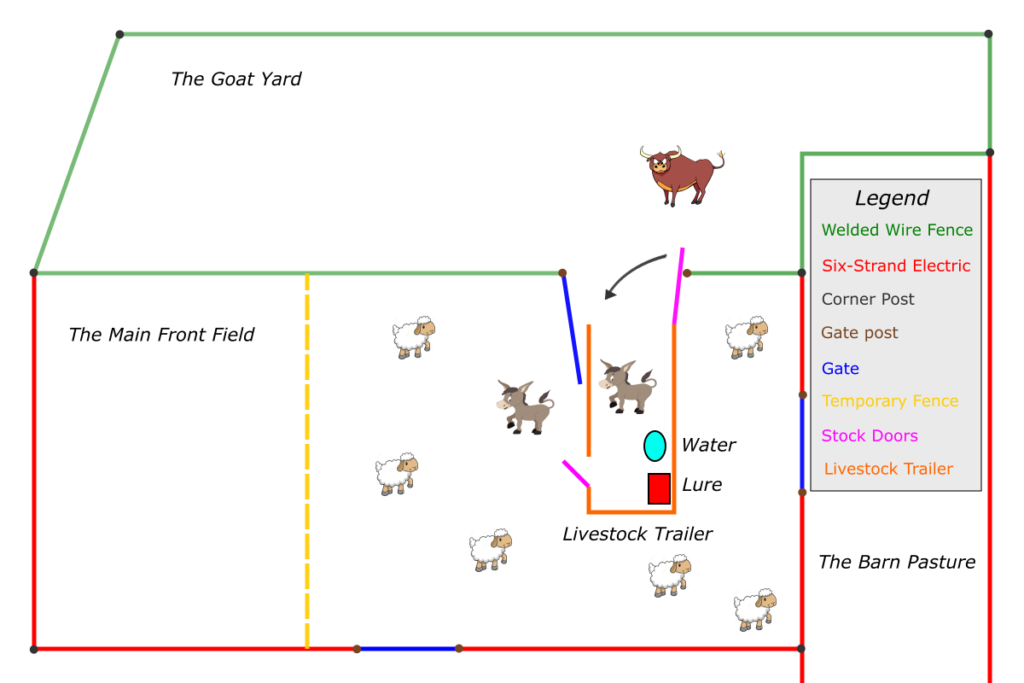

The flerd had been in the goat pen for a few days. The goat pen was this little half-acre paddock that I built years prior when we tried our hand at meat goats. It was this little section that wasn’t quite pasture and wasn’t quite forest, that lovely little mix of multi flora rose, privit, blackberries, and a bunch of other pioneer species that I wasn’t familiar with. I had built a five-foot tall, 4”X2” welded-wire fence secured with T posts and let some goats have at it. The meat goat venture ran its course and the farm was left with this cool little paddock in a transitional location between the main pasture and the woodline. Normally, there was only about 12 hours worth of forage in there but I prolonged their stay by feeding hay for an extra day to add to the animal impact and lay down some more carbon. It was worth it to keep that area leaning toward growing grass as opposed to forest, without having to get in there with machinery and rip all that brush out. Livestock like to move, and they like to eat green grass when they have a choice, so I knew they would exit the goat pen with no fuss, but I was gonna throw a little curve ball at them.

I went and got the livestock trailer and set it up just outside the gate to the pen. I put up a strand of temporary netting for their next paddock, and I even had a little sweet feed laying around I took with me. Nothing was different except the trailer being in between where they were and where they wanted to go. I opened the big back loading door and the small pedestrian door on the front passenger side and hid. I went outside to the front of the trailer and laid underneath it on the ground completely out of sight from all the animals and waited, quietly. The donkeys were the first to go through. No hesitation to speak of, they went to the back of the trailer and kinda stared at it for a moment, then hopped right on and went right out the front door into the new paddock and began grazing. All I could really see was a bunch of hooves scurrying along. My point-of-view was fairly limited from underneath and as soon as the sheep watched the donkeys pass through unscaved and start eating, they soon followed. It was fun to hear the flock scamper on the floor just inches above my head. I was feeling rather proud of myself, so-far-so-good. In the moment, my efforts at concealment were thus far paying off, but I had learned many times over not to get too confident. At this point, Big White was not where I wanted him to be, and the scoreboard had him winning and me losing by a landslide.

My plan went something like this: as soon as he got all four feet on the trailer, I would spring up and close the pedestrian door, then dash to the back as quickly as I could and close the back door. I layed there, out of sight, no movement, no sound and peeked out as I watched him start galloping back and forth in the paddock. One thing these herd animals really don’t like is to be alone. With the rest of the flock in plain sight, happily and calmly grazing along, all he had to do was walk through the trailer to cross the threshold. That was the last option in his mind though. He ran fast as he could all along the inside of the goat pen just looking for an alternate route, and I knew that he could jump fences because he’d done it many times in the past. At 1800 pounds, my little goat fence wouldn’t stand a chance. Right when I was thinking about all that he took a full fledged sprint straight toward the fence and I knew he was going to jump right over it and all I could do was sit there hidden and watch. In addition, if he jumps over this fence and sees my lying under this trailer trying to be all sneaky, I’ll really have my cover blown. It would just be another victory for the steer – chalk one up for him again. To my amazement, right in the very moment when he would have jumped, he stopped. He stopped and checked out the trailer, sniffing it and pacing behind it. After he calmed down a bit, I could see his feet getting real close to stepping up there. I could see he had his head in and was considering going in; there was hesitation, and I thought maybe he could smell me and I was adding to his suspicion.

I figured he was getting pretty stressed again. After that last episode, I thought to myself: not having caught the steer is different than not having caught the steer and having him jump another fence, and then having to go fix it. So, I decided to go back to the drawing board – maybe some other opportunity would arise and I’d have better luck. I got up and walked toward the truck, all set to hook up to the trailer and move it out of his way when I said to myself: “You know what. If he wants some damn grass he can walk through that thing and get it himself and if he hops another fence, so be it.” I got about 40 yards away and sat and watched. It was close to sunset by now and that little spot on the farm has great western exposure. The peacefulness of the sheep and donkeys grazing in the cool air with a watercolor-painted sky was quite tranquil. The ease only disrupted by big white still pacing back and forth in the goat pen looking for a way out, any way out other than through the trailer. Just as I figured I better get the truck and let him settle, I was astonished to watch him suddenly walk right through the backdoor and straight out the front. It was a decisive move, almost as if he shrugged his shoulders and just went for it. I guess he got tired of watching all his compadres eating grass and felt he was missing out on the fun. I was so relieved to see it happen, thankful to witness him conquer his fear and pass through, but it didn’t get me any closer to achieving my goal.

So now he is out with all the sheep and two donkeys, I let him settle down a bit after he started grazing and he looked perfectly content, all was calm. He really had to pump himself up to go through the trailer, so I knew I didn’t have a prayer of getting him back on tonight. Besides, it was getting dark and I would have to set up a whole new configuration to even try. I headed back toward the barn, with my chin on my chest a bit feeling like I had lost yet another battle with the steer – a feeling I was too accustomed to. On the way back I remembered the half bag of sweet feed and an empty feed bucket. I eased back through the flerd with the sweet feed and they were so content nobody really paid me any attention. I took a little detour to the donkeys who hang out together in the field. They have been around the block on the farm, in fact the older one was here before me so I thought I’d give them a little treat just because I had the opportunity to do so and they practically never get any sweets. I’m scratching their ears with one hand and feeding them with the other when low and behold, big white looks at me, smells the air and takes a step or two in my direction. Quick and calm, I placed the feed inside the front pedestrian door, went to the back and closed the big door and sat off in the corner to see what would happen. I put the feed all the way inside the pedestrian door as far back as I could. If they wanted it they would have to step up in there and get it, not stand outside with their feet on the ground and stick their heads in. This would prove to make a big difference.

The donkeys practically followed me on the trailer, soon as I set the feed down they were on it. The two of them shoulder to shoulder eating out of a bin in a corner creates a touch of a competition. Healthy rivalry among the animals isn’t a bad thing and it worked in my favor because Big White was easily twice their size, but the treats were in short supply. I was well out of the way back to my 40 yard spot to make sure no matter what happened, I wouldn’t interfere. Sure enough, Big White followed his nose down there and looked in the trailer to see the two donkeys having a grand time eating what is essentially ice cream to livestock.

A couple key things happened next: first he stuck his head into the trailer, then he put it as far in the trailer as he could without stepping in. He still couldn’t quite reach the feed, at least reach it and enjoy it comfortably with two donkeys in his way. I worried that they would run out, I didn’t put that much in the bin, just a treat and if I ran down there and spooked them by trying to add more, I would risk blowing the whole thing. I think the urge to have a couple good satisfying mouthfuls was enough to convince him, and considering he had just been on the trailer and nothing remotely bad happened, he had no reason to associate it with any danger.

My excitement, anticipation and heart rate were all on the rise. Here he was with his whole head in the space where I wanted him, I’d never been so close. No noise, no people clapping and screaming, no chains banging on metal, none of the things you know would spook livestock, just a little bit of feed and me well out of the way. Then it happened, he put his two front feet on the trailer. I couldn’t believe it! So close! I flew down there as fast as I could and I never made a sound (yes I’m bragging a bit on that one) careful to stay completely out of his sight path should he look up. I positioned myself a few feet away, trying hard to remain calm, a lot could still go wrong here but then… yes! He took a full step forward, all the way into the corner to get complete access to the feed while the donkeys had to wait their turn. Now I am inches from him, he still doesnt know I was there and I’m face to face with his rump, which is as tall as I am. It was really exhilarating, nearly a year’s worth of failures had all accumulated to this very moment, and I had to play it right, my one chance! He was mostly in there but not all the way, two back feet still on the ground, how can I get him up there, and without thinking about it I slapped him on the ass as hard as I could and he jumped right on the trailer! I had that door closed in the blink of an eye and nearly had what felt like a panic attack but with excitement. I must have ran around that thing checking the doors and latches at least a dozen times. With him loaded and the trailer secure I finally had him. Having lost every previous battle, that evening I won the war.

The next day I called the abattoir first thing and happily reported that the steer that had been alluding me this past year was loaded and ready to go and could they please find an opening for me. To my surprise, they had one the next day, so I filled a water trough for them and parked the trailer in the shade. The donkeys would simply have to go for a ride. The slaughterhouse has a great handling facility and when I got there we put them back on the trailer with no difficulty whatsoever. When I got back to the farm, they went back in with the sheep and are still out there grazing right now as I write this.

As previously mentioned, most steers are finished at 1200 pounds live weight. After they are eviscerated, the carcass hangs on the rail in a cooler for 10-14 days. This is called the hanging weight, typically 60% of the live weight, typically somewhere around 700 pounds. Then after the carcass is butcher, you end up with roughly 500 pounds of actual meat. Another way to consider it is 40-30-30. Forty percent skin, bodily fluids, hair, etc. Thirty percent bones, and thirty percent meat. When I went to pick up Big White he had hung on the rail at 1,020 pounds, 300 pounds over average.

This all happened about 8 or 9 years ago and since then I have loaded, moved, worked with and harvested many animals. I’ve never had one that was that untrusting and fearful. All the livestock I have since worked with display similarities at times but never to that extreme. I’ve had a few old-timers tell me you always get one like that. This makes sense if you think about it. When you are around animals all your life and they are constantly coming and going, consider the one that was the most difficult, its bound to happen in life that some animals are easier to work with that others

I’m thankful for that steer. Thankful for the lessons he taught me about low stress handling. His hypersensitivities forced me to treat him gently and with great care, in a way he kinda taught me about trauma. If I had chased him, or used cattle prods, or constantly yelled and scrambled at him I have every reason to think he would have been even more difficult to work with even more stressed. I have no interest in making any animals’ lives stressful, just the opposite. If the goal is to understand as much as we can about livestock and try and work with them to regenerate our lands, not depreciate them, and only in the end to transition them into food we serve our friends, families, and customers, they absolutely deserve the best possible life we can give them. He taught me that I’ll never know what an animal wants more than the animal itself and so it becomes my job to observe and provide.

There is an element to farming that I think all producers experience in different ways and at different times. A feeling of trying to control things you don’t have control over. Sometimes it goes the way you want and you feel on top of the world, other times things don’t pan out and you have to succumb and show up tomorrow to try again. Over the years, the more I remove my intentions, the more I try to let nature show me what it wants, the more I’m able to plug-in and achieve cohesion, the more success I have. The animals are my greatest teachers, I hope it stays that way.